This is part II in an ongoing series of excerpts of an article set to be published this summer in The International Journal of Architectural Research, tentatively titled The Principles of Emergent Urbanism. Click here for part I, The Journey to Emergence.

The qualities of an emergent city

The adoption of mass-production processes, or development, in substitution for spontaneous urban growth in the mid-20th century created for the first time a phenomenon of alienation between the inhabitants and their environment. While the physical features of spontaneous cities could be traced to complex histories of families, businesses, and organizations, the physical features of planned cities owe their origin only to the act of planning and speculation. This has severe consequences towards the sustainability of place as there will not grow any particular attachment by the residents, their presence there being only a temporary economic necessity and not the outcome of their life’s growth. Mass-production of the environment left people as nothing more than consumers of cities where they used to be their creators. A building culture was replaced with a development industry, leaving the landscape culture-less and with no particular sense of identity. This took place despite the evidence that a building which has a unique history and has been fitted to someone’s life, as opposed to speculatively produced, generates market value for that property. (Alexander, 1975) This is why, although the demolition of so-called “slums” to replace them with modern housing projects created a great deal of opposition against urban renewal programs, the demolition of the housing projects later on did not lead to a popular preservationist opposition. They were not the physical expression of any culture.

In additional to cultural patterns, spontaneous settlements also have a peculiar morphology that has not successfully been imitated by modern growth processes. Spontaneous settlement processes give individuals full freedom to determine the boundaries of their properties. Spontaneous settlement is one where total randomness in building configuration is allowed, with no pre-determined property lines acting as artificial boundaries. Buildings and building lots as such acquire general configurations comparable to cell structure in living tissues, unique sizes and boundaries that are purely adapted to the context in which they were defined. In the absence of abstract property boundaries, property rights are bounded by real physical limits such as a neighbor’s wall. (Hakim, 2007)

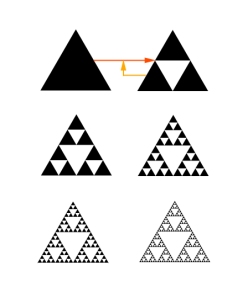

Very attractive spontaneous cities have a specific pattern of the urban tissue. It consists of similar vernacular buildings that appear very simple when considered individually, but produce a visually fascinating landscape when considered as a whole. This is a form of fractal geometry. In mathematics a fractal is a geometric object of infinite scale that is defined recursively, as an equation or computation that feeds back on itself. For example the Sierpinski triangle is defined by three triangles taking the place of one triangle as in figure 4.

Figure 4. A triangle triggers a feedback function that produces three triangles, which themselves trigger the feedback function to produce nine triangles, and so on. This process can unfold as long as computational resources can be invested to increase the complexity of the object.

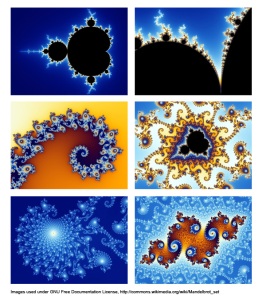

The Mandelbrot Set is a much more interesting fractal that is defined as a simple recursive mathematical equation, yet requires a computation to visualize in its full complexity. When computing how many cycles of feedback it takes for the equation to escape to infinity for specific coordinates, figure 5 is the outcome.

Figure 5. The image on the right is a deeper magnification of the image on the left, produced with a narrower range of coordinates as the input of the Mandelbrot set’s feedback function.

In addition to its remarkable similarity to natural phenomena, this form of geometric order informs us of a very important law in geometry: a feedback loop that is fed through the same function will produce an ordered but unpredictable geometric pattern out of any random input.

This tells us why cities of vernacular buildings have such appealing geometric properties at the large scale, despite being often shabby and improvised at the scale of individual buildings. Shanties made of scrap metal and tarp look rough at the scale of the material, but because multiple shanties share the construction process and originate from similar feedback conditions they form an ordered geometric pattern with its specific “texture”. The same process takes place at other scales of feedback, for example the production of a door. Whether the input for one door is larger, taller, wider than another door, if the same production process is employed the two doors will contribute to the overall fractal order of the urban space. This law has been employed not only in traditional and spontaneous cities, but also for modern urban planning initiatives. In the New York City neighborhood of Times Square the structure of billboard advertisements is defined by a building code that determines their configuration in relation to the configuration of the building. The outcome is a unique tissue of advertisement billboards that has become more characteristic of the neighborhood than the buildings themselves, which are not produced by a shared feedback function.

Fundamentals of urban complexity

Christopher Alexander showed in A City is not a Tree (Alexander, 1965) that social and economic networks formed complex semi-lattice patterns, but that people who observed them limited their descriptions to a simple mathematical tree of segregated parts and sub-parts, eliminating connections in the process. (Figure 6 compares the structure of a tree and semi-lattice.) In attempting to plan for urban structure, a single human mind, without a supporting computational process, falls back on tree structures to maintain conceptual control of the plan, thus computing below spontaneous urban complexity, a phenomenon that is consistent with Wolfram’s theory of computational irreducibility of complex systems. (Computational irreducibility states that the only accurate description of a complex system is the system itself and that no abstraction or reduction to a simpler process is possible.) Nikos A. Salingaros later detailed the laws of urban networks in Theory of the Urban Web. (Salingaros, 1998) Network connections form between nodes that are complementary, and therefore the complexity of networks depends on an increasing diversity of nodes. Salingaros describes the urban web as a system that is perpetually moving and growing, and in order to do this the urban tissue has to grow and move with it. Consider for example the smallest social network, the family. Debate over accessory units or “granny flats” has intensified as normal aging has forced the elderly out of their neighborhoods and into retirement complexes, while at the other end of the network young adults entering higher education or the labor market vanish from a subdivision, leaving a large homogeneous group of empty-nesters occupying what was once an area full of children, and often forcing school closures (a clear expression of unsustainability).

Figure 6. A comparison of a tree pattern on the left and a semi-lattice pattern on the right. The tree structure is made of groups and sub-groups that can be manipulated separately from others. The semi-lattice pattern is purely random without distinct sub-parts.

These social networks grow more complex with increasing building density, but a forced increased in density does not force social networks to grow more complex. For instance the spontaneous settlements of slums in the developing world show remarkable resilience that authorities have had difficulty acknowledging. Because of squalid living conditions authorities have conducted campaigns to trade property in the slum for modern apartments with adequate sanitary conditions. To the authorities’ befuddlement some of the residents later returned to live in the slum in order to once again enjoy the rich social networks that had not factored in the design of the modern apartments and neighborhoods, demonstrating that the modern neighborhoods were less socially sustainable than the slums.

In commercial networks, space syntax research (Hillier, 1996), using a method for ranking nodes of semi-lattice networks, has shown that shops spontaneously organize around the multiple scales of centrality of the urban grid at its whole, creating not only commercial centers but a hierarchy of commercial centers that starts with sporadic local shops along neighborhood centers and goes all the way to a central business district located in the global center of the spatial network. The distribution of shops is therefore a probabilistic function of centrality in the urban grid. Because the information necessary to know one’s place in the hierarchy of large urban grids exceeds what is available at the design stage, and because any act of extension or transformation of the grid changes the optimal paths between any two random points of the city, it is only possible to create a distribution of use through a feedback process that begins with the grid’s real traffic and unfolds in time.

The built equilibrium

Although they may appear to be random, new buildings and developments do not arise randomly. They are programmed when the individuals who inhabit a particular place determine that the current building set no longer provides an acceptable solution to environmental conditions, some resulting from external events but some being the outcome of the process of urban growth itself. It is these contextual conditions that fluctuate randomly and throw the equilibrium of the building set out of balance. In order to restore this equilibrium there will be movement of the urban tissue by the addition or subtraction of a building or other structure. In this way an urban tissue is a system that fluctuates chaotically, but it does so in response to random events in order to restore its equilibrium.

This explains why spontaneous cities achieve a natural, “organic” morphology that art historians have had so much difficulty to describe. Every step in the movement of a spontaneous city is a local adaptation in space and time that is proportional to the length of the feedback loops and the scale of the disequilibrium. For spontaneous cities in societies that experience little change the feedback loops are short and the scale of disequilibrium small, and so the urban tissue will grow by adding sometimes as little as one room at a time to a building. Societies experiencing rapid change will produce very large additions to the urban tissue. For example, the skyscraper index correlates the construction of very tall buildings with economic boom-times, and their completion with economic busts. The physical presence of a skyscraper is thus the representation of a major disequilibrium that had to be resolved. (Thornton, 2005) The morphology of this change is fractal in a similar way that the movement of a stock market is, a pattern that Mandelbrot has studied. In general we can describe the property of a city to adapt to change as a form of time-complexity, where the problems to be solved by the system at one point in time are different from those to be solved at a later point in time. The shorter the time-span between urban tissue transformations, meaning the shorter the feedback loops of urban growth, the closer to equilibrium the urban tissue will be at any particular point in time.

Modern urban plans do not include a dimension of time, and so cannot enable the creation of new networks either internally or externally. They determine an end-state whose objective is to restore a built equilibrium through a large, often highly speculative single effort. They accomplish this by creating a large-scale node on existing networks. In order for such a plan to be attempted the state of disequilibrium in the built environment must have grown large enough to justify the immense expense of the new plan. This is why development will concentrate very large numbers of the same building program in one place, whether it is a cluster of 1000 identical single-family homes or a regional shopping mall, just like the skyscraper concentrates multiple identical floors in one place. Demand for these buildings has become so urgent that they can find a buyer despite the absence of local networks, the standardized building plan, or the monotonous setting. This is not as problematic for large cities for which a single subdivision is only a small share of the total urban fabric, but for smaller towns the same project can double the size of the urban fabric and overshoot the built equilibrium into an opposite and severe disequilibrium.

The mixed-used real estate development has attempted to recreate the sustainable features of the spontaneous city by imitating the morphology of sustainable local economic networks. It has not reintroduced the time dimension in economic network growth. Often this has resulted in a commercial sector that serves not the local neighborhood but the larger region first, consistent with the commercial sector being a product of large-scale economic network disequilibrium. In other developments the commercial sectors have struggled and been kept alive through subsidies from residential development, which is evidence of its unsustainability as part of the system.

References

Alexander, Christopher (1965). ‘A City is not a Tree’, Architectural Forum, vol. 122 no. 2

Alexander, Christopher (1975). The Oregon Experiment, Oxford University Press, USA

Hakim, Besim (2007). ‘Revitalizing Historic Towns and Heritage Districts,’ International Journal of Architectural Research, vol. 1 issue 3

Hillier, Bill (1996). Space is the Machine, Cambridge University Press, UK

Salingaros, Nikos (1998). ‘Theory of the Urban Web’, Journal of Urban Design, vol. 3

Thornton, Mark (2005). ‘Skyscrapers and Business Cycles,’ Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, vol. 8 no. 1

Wolfram, Stephen (2002). A New Kind of Science, Wolfram Media, USA

Comments

Nice post. I really enjoyed this and look forward to the next installment.

I do take issue with a couple statements, however.

"But for smaller towns the same project can double the size of the urban fabric." This seems unlikely. Do you have evidence of this actually happening?

"The adoption of mass-production processes, or development, in substitution for spontaneous urban growth in the mid-20th century created for the first time a phenomenon of alienation between the inhabitants and their environment. " Again, this seems like pure speculation. It hardly seems likely that no one was alienated from their environment prior to 1950. Consider the factory towns of the 19th century, especially the giant dorms of New England factory towns. These were not constructed incrementally by individuals, but were built en masse by factory owners.

One theme I notice in many of your posts is the idea that the planning/development system shifted from an individual-based system to a corporate-based system, dominated by developers, in the mid 20th century. But you never explain why you think this, and you seem to ignore the fact that developers played a large role in development prior to 1950 as well.

For example, Birmingham, Alabama, my home town, was developed in the 1870s and 1880s by industrial developers around steel mills. The land for the entire city was purchased by developers and subdivided into a system of blocks by the developer. So the developer owner the land. The developer subdivided the land. The developer sold the land. Individuals purchased the land and constructed the buildings, but they likely needed bank loans to do so.

So, while development happened more incrementally, banks and developers still controlled a great deal of development. This doesn't look much like the spontaneous slums you write so fondly of. And it seems unlikely that any significant permanent development in the US and Western Europe has happened spontaneously since the middle ages. Can you address this?

Have been reading this blog for a while, and always enjoy your posts. Interesting comments by Patrick as well -- I can't speak much for Birmingham, but in my city of Nashville the process of development, from the 1750s to the 1950s and later, also involved a large degree of top-down planning.

The main differences from today were that 1) neighborhoods were built on tight grids around some existing infrastructure, rather than as isolated greenfield developments, and 2) although large developers bought farmland, subdivided it and sold it as early as the 1850s (even the CBD was created through a similar process in the 1780s), they did not actually build the houses themselves. My own street, very near downtown, was platted in the 1880s, with the first house completed in the 1890s, and the last vacant lot built on only in the 1960s. I think this is all fairly typical of the older portions of American cities.

While it's certainly not anything like a spontaneous process -- zoning laws would have stopped that 80 years ago regardless -- the responsibility for the bulk of the built environment was nonetheless on the individual. You can still see evidence of this today in the dedication plaques on old commercial structures, which contain the name of an owner and the year the structure was built, indicating pride in the building and in individual ownership. The last one I have seen downtown is dated 1957.

Patrick makes an excellent point, but I think the differences in the pre-1950s pattern of urban development are fairly significant. I agree, though, that it would be going too far to imply that the the old process was "spontaneous."

There is no strict dichotomy between a spontaneous and planned city. There is a spectrum. As I've argued before, every city needs to have an emergent dimension at some scale in order to continue functioning through environmental change. While the completely random city of the middle ages was fully emergent, from the shape of the landscape to the details of buildings, early city planning efforts mostly limited themselves to define a landscape structure such as an orthogonal street grid.

A very significant threshold was passed, however, when the land developer as a subdivider was transformed into the land developer as real estate salesman. Subdividing land has always been part of the process of urbanization, and many of the patterns of spontaneous cities can be explained by property owner subdividing their lots to increase the density and benefit from the higher demand for urban land. 19th-century regulations obliged land subdividers to uphold street grids, but the idea of "infrastructure" was not well-developed, and in fact streets were typically nothing more than dirt paths that required no investment.

It was the advent of infrastructure and municipal utilities that forced land subdivision to become today's development industry. Municipalities wondered how the extension of utilities and public services were to be paid for. The solution was to impose the costs onto developers, who were required to build infrastructure to regulation and turned to the banks to finance this additional work. What it meant was that the growth of the neighborhood had to be rapid enough to pay for all these utilities and it could not exceed the density for which the development was planned, which would impose higher costs on the municipality once the developer had long moved on. The developer therefore had to sell a lot of homogeneous houses very quickly, and those houses remained there ever since.

This is not to say that large-scale real estate development did not exist prior to the 20th century, as Patrick points out. But the concentration of capital necessary to realize them was quite rare during the 19th century, available at first only in England and then spreading to other countries gradually. The story of the renovation of Paris involves large banking oligarchies partnering with the prefecture to build new streets, and while these streets today are considered to be some of the most beautiful in the city, built with all the craftsmanship of 19th-century industrial production, they are not the most alive. They succeeded because they were inserted within the tissue of a spontaneous city and therefore came to complement it. New neighborhoods in the suburbs did not have this advantage, and unless they were close to a traditional village, still to this day do not have much life of their own.

In North America capital concentration came even later, the Federal Reserve System founded in 1913 and the Bank of Canada in 1935. Without this funding the modern system was not possible, and people who wanted to borrow to build a house had to borrow the savings of their neighbors through the local small-town bank.

This is an interesting post (the comments as well) but I think you miss some important societal trends that were based mainly on technological innovation. Most importantly, the way people shared information now is much closer to the way it was shared before the advent of homogenized and mass produced TV and radio.

Twitter, facebook, blogs, etc... are a technologically advanced form of a 18th century town hall meeting or conversation over a beer. Contrast that with 20th century TV and radio (and even most of the newspaper) which is much more like listening to a speech, or rather, speech after speech after speech.

Modern suburbs don't lack fractal or emergent qualities, they are just much much simpler than their predecessors because fewer voices were involved in crafting the rules.

In the 50s, people bought into the big yard and white picket fence not because that was the most wonderful thing, but because it was cheap for developers with cheap land outside cities to control public opinion.

As we begin to add new rules--informal or otherwise--and not merely add complexity to the existing ones, we have a chance to alter the entire development process. We can promote pedestrianism or sustainability, health or investment.

Any disagreements aside, I really appreciate the level of dialog you promote here, Mathieu. It is quite unusual for an author to respond so thoroughly and respectfully to comments, but it is very valuable. Thanks.

Matthieu, I started reading the blog a couple months ago and always find your articles refreshing and provocative. As a RE banker who finances large developers, I think most of the criticism of modern real estate development industry is spot on. Just a couple of my own observations , keeping in mind I'm not a planning professional-

I think what Patrick is getting at is that you need to recognize how the transition from merchant/agrarian capitalism to industrial capitalism played a big part in altering the process of urban growth. Changes in the scale of production and the concentration of capital did allow for the "natural" emergence of factory towns and other forms of dictated development. They were natural in the sense that they grew in the absence of government planning. Yet your narrative starts more than a century later with the introduction of the first modern suburban subdivision (or so I assume that's what you are referencing). By doing this you pass over a lot of history where government planning evolved in response to correct the pathologies generated by industrial development. This is unfortunate, because I suspect that this period represents an instructive middle ground for planners and developers trying to find the right trade-off between spontaneity and predictability.

The Birmigham development process that Patrick describes sounds like a decent blend of the two, which is to say it allows for much more spontaneity than your typical master-planned subdivision. The developers (and builders subsequently) did not have to zone the land, get planning commission approval, defend their plan at public hearings, apply for permits, conduct environmental impact assessments and traffic studies, and pay hefty "impact fees" to grease the palms of local officials. And as CG points out, the very idea of starting a new town based on a grid, then allowing the land developers to sell to builders who had mostly free reign is a foreign concept to modern town planning regimes.

Thanks for giving a clear view on the fundamentals of this.

Having read and been influenced by A City is not a Tree some years ago and by some of the writing of Nikos Salingaros, I have always wondered whether the same topology and algebra can really be used at the level of the building, of the city, and of social networks. I make the simple observation that within the past century we have gone from a grid pattern for streets and elegant hierarchical arrangement of elements at different scales for buildings to a grid pattern on buildings and elegant looking road hierarchies.

And they are only simple examples, but a lot of fractals, including Sierpinski carpets and the Mandelbrot set are actually hierarchical. Show me a city based on a Julia set with an infinity attractor and I'll say "uncontrolled sprawl", but pretty from the air.

So while a building facade probably gains from being scale invariant to a degree and having a bit of a fractal dimension, I'm not convinced that the same necessarily holds at the urban scale. For one thing, social networks are no longer as localized as they once were, and I would refer you to Barry Wellman's work on locality. Urban space is only locally metric, and measures of distance vary according to means of transportation and communication. Stores and friends can be close by foot and far by car or vice-versa based on several factors controlled by planners. But Facebook and eBay are always the same distance.

A city is always responding to changing conditions, but I am not certain the response necessarily restores an equilibrium. So for instance a random fluctuation can create a local demand for a rendering plant or a bagpipe school, things that have a negative impact on neighbours. Satisfying demand, in the absence of planning, can create its own dislocations, with people who can afford it gradually moving away over a period of years. Emergent phenomena are not necessarily static solutions even long after the perturbation is gone. That's not necessarily bad, but what I don't like is the cyclical theory of urban development, where it is believed that a community must fall into decrepitude and then be redeveloped as a natural cycle. This is only applied to dispossess the poorest communities and hand them over to developers. This type of feedback cycle (poor=bad, rich=good) tells me something is broken in the system, where a drop in land prices through the mechanism of human misery is required in order to restore overall equilibrium.