There is a scene early in the 2006 mockumentary Radiant City that provides the key explanation to the morphology of suburban sprawl. Our favorite writer James Howard Kunstler sits on a bench in a community bike trail that is enclosed in two rows of chain link fence in order to, I presume, secure it from the high-capacity arterial road that runs alongside it. The experience is vaguely what it must have been like to patrol the Berlin Wall, had it been encircled by an expressway. "Some clown in an office somewhere thought this would be a good idea, that's why it's here," says Kunstler. "Not because anybody really tested whether or not it would feel good to be here."

That's all the film has to say about why sprawl is, and in fact there is nothing more to be said. The characteristic of a sprawl city is the absence of any intelligence in design. The rest of the movie is about how and why families cope with life in this intelligence-less environment. It does that with a narrative that is refreshingly honest and modern, despite not depicting a real family. It is shot on location in the outskirts of Calgary, a city that, thanks to a highly competent planning authority and an economic boom that has attracted large numbers of new citizens, has over the last decade built new developments at supernaturally huge scale.

The new neighborhoods are for the most part built of nice buildings, nothing to write UNESCO about but approaching genuine Victorian. Contrary to the suburban cliché, houses are built to a density that is comparable to city centers, which means there is adequate public transportation available. And in compliance with new planning regulations, developers have provided big clusters of condominium buildings to serve as "affordable housing". With this setting, the directors have avoided the social exclusion issues that sometimes get bundled up with criticisms of the suburbs. In fact here the families explain that they left the center because it had become unaffordable for either their growing family or without shame-bearing subsidization (never mind affordable housing regulation being indirect subsidization), meaning the exclusion narrative is turned backwards. These people have been pushed out of the city.

What is there left to complain about then? Not very much, still there is a general awareness that there must be something missing, yet none of the characters can pinpoint it. They deal with boredom as best they can, the local teenagers finding, as all boys have ever done, that a muddy pit is all that's needed for endless fun. Today's boys turn this free space into a paintball game they call "escape to Mexico", but it's really just cowboys and indians for the postmodern age. Their fun is interrupted by a private security patrolmen hired by the builders to patrol the private streets, but these guards turn out to be benign bordering on benevolent. Incessant chauffeuring becomes the cause of a mini-crisis as poor husband Evan is forbidden from working on his car by his emasculating witch of a wife Anne, worried that such activities will send the car to the mechanic and leave her with the entire burden of chauffeuring the family on their maddening activities schedule.

If there is one recurring theme, it is that at every point the creative control of the environment has been taken away from individuals. The kids cannot play on empty lots, the father cannot risk working on his car, the space for any meaningful personal culture has been slashed to nearly nothing. The exception to this is Anne who gets to enjoy total control of the house itself, which she obviously takes great pleasure in when deciding how each room will be laid out. At every point in the film where someone defends the choice of life in the suburbs it is either Anne or a female real estate agent involved.

As a form of passive-aggressive revenge, Evan signs up to be in a musical about suburban life where he and his male friends sing showtunes while dancing around with lawnmowers. (Lawnmowers having no utility in the postage-stamp sized lawns of the new suburbs, they are remembered in dance.) It is telling that Evan found out about the show by looking around the Internet. It is on the Internet that community and culture has exploded in the last years as the physical world has become more and more inaccessible. The Web 2.0 phenomenon has given the power to everyone to create something and express themselves, for better or worse. The Web has become a new city, and its different processes new forms of urbanism.

Sorely missing from the film, which features the opinions of architects, professors of philosophy and other intellectuals, are the opinions of the planners, politicians and developers who make this product. The planning system is as remote to the narrative as it is to people's lives. While the complaint of the loss of citizenship implied by mass motorization is rehashed by an intellectual, what about the loss of citizenship implied by the planning process itself? All decisions about the shape of their environment has been taken long in the past, in the colorful words of Mr. Kunstler, by some clown in an office somewhere. The only thing left for citizens to do is to enjoy or hate their environment. They have been dispossessed of any power to shape it. Somewhere democracy of place was substituted for bureaucracy, and the best the citizens have been offered since is the chance to collectively shackle the bureaucrats through public design charrettes. The citizens have no more rights to create their city than citizens of Stalin's Moscow did. That is the only aspect sprawl still has in common with Le Corbusier's original vision for the Radiant City.

Yet the film does not reach this conclusion. If there is any conclusion, it is that everyone is helpless in the face of this seemingly unstoppable monster. As Joseph Heath says at the beginning, the critique of suburbia is the same it was two generations ago, everyone who lives in suburbia knows backwards and forwards the critique of suburbia, yet they still live there. Andrès Duany appears proposing that what sprawl needs is a grid and denser housing, yet the setting already has a grid and obviously the last thing it needs is even more houses.

A young woman states at the end, out of character, that she sees kids playing alone in suburbia and remembers her youth building giant forts with everybody in the neighborhood. I remember my happiest time growing up at the edge of the suburbs was building a treehouse on some leftover tree with the neighborhood kids. The treehouse was demolished because it was unsafe and then the tree cut down to build another house. I never saw any of those kids again.

That's all community is, people making things together. That's what creates the spiritual aspect of a place. Once we lose the freedom to do that, we can't be citizens. We are just consumers of cities. Radiant City, by looking at life in suburban sprawl in its purest, best realized form, defines the right problem but fails to ask the right question. Perhaps citizenship is so far in the past that we can't even remember to ask the question.

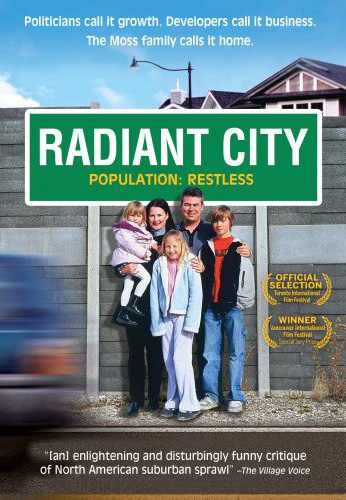

Radiant City

A film by Gary Burns and Jim Brown

Comments

You should come visit Detroit, community is all that remains.

Interesting observations, and in general I agree. However, I would add that another powerful part of this film is the dystopian idea that in a "dis-aggregated" world of suburban limbo, violent death is inevitable, and often emerges out of sheer boredom. One woman claims she fled the city to escape violence, but we are shown clearly how the only way for the young boy and his comrades to feel something in the anesthetized landscape of suburban sprawl is to commit increasingly dangerous, violent acts. Climbing a cell phone tower to spy on neighbors, war games, execution as a form of entertainment, and finally the killing the young boy's sister with "dad's gun". This is the same thesis running underneath Richard Linklater's film "Slacker". The pervasive fear of violent death that emerges from false community. I love this movie. It's a mockumentary version of the fictional TV show "Durham County". A clever work of speculative fiction that is undeniably true enough to stimulate real shivers.