Review of The Architecture of Community - Léon Krier (2009), Island Press

Review of The Architecture of Community - Léon Krier (2009), Island Press

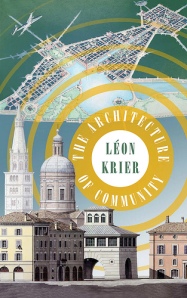

The Amazon Santa visited me this year and left Léon Krier's latest, and likely ultimate, publication, The Architecture of Community. (Thanks to those who made generous purchases on the Emergent Urbanism Amazon Store, remember that you can also purchase anything at all.)

Back in the 1970's when architectural modernism began to fall apart or be outright demolished, the architectural intelligentsia decided that it was okay to start using ornament again, to make buildings flashy, to take the dry structures of modern buildings and decorate them with absurd icons whose purpose was to entertain long enough that no one would notice that the architecture was still terrible. Léon Krier, a renegade amongst renegades who had no formal architectural education, had an other idea in mind: that there was such a thing as objective laws in architecture, that these laws remained unchanged over time, and that classicism was the best expression of these laws. Any other architect's career would be destroyed by such a claim in such an era - Léon Krier just kept going, publishing article after article, book after book, until the estate of the Prince of Wales gave him his big break and commissioned the design of an entire neighborhood based upon his ideas. If there is a neo-traditionalist movement in architecture and urban design today, it is because Léon Krier imagined it first. This book is the compilation of the product of his career as an architect, but mostly as a writer.

Having read through the book, my conclusion is that Krier gives a thorough lesson in architecture, taking obvious pleasure is shredding the myths of modernism to pieces and exposing its false prophecies. However, the text never goes beyond the most superficially descriptive, often involving comparisons and an appeal to common sense. While Krier can point out, using his trademark caricatures, how absurd the patterns of modern sprawl are, he has no explanation as to why such patterns would exist, except that it may be just one big conspiracy. He has even less to say about community, which is strange considering the word is in the title. It is as if in the vocabulary of neo-traditional architects community and space have become synonymous. (Many of the great villages and towns of Europe are dying because their community is dying, regardless of their physical form.) For this reason Krier produces a very sharp lesson in architecture, but provides no insight into morphology, and cannot really develop a model of urbanism that isn't simply architecture at enormous scale. It should be no surprise that his disciples have practiced town planning the same way.

Despite his claims of providing a plan for the post-fossil fuel age, his projects require enormous concentrations of capital to develop, the kind of capital only princes have at their disposal, and provide no guarantee of ever being home to a true community. Although he demonstrates a sensibility, if not necessarily an understanding, for chaos theory and complexity, I am left wondering if he refers to it because he finds it convenient, or because it is true. He points out that fractal geometry has denied modernism the use of abstract forms as more rational geometric objects, and many of his drawings could be used as perfect examples of complex geometry. It is however not explained why anything is depicted the way it is, or how it could be the way it is. Architectural complexity is embraced, but the leap to emergence, crucial for any practical model of urbanism, is not there.

Most of the book consists of sketches, pictures and small essays whose intent is to persuade instead of to argue, and there lies the most peculiar thing about it. It is in precisely the same format that Le Corbusier once published his works of pioneering architectural propaganda. It is as if Krier sought to turn the very arms of modernism against it, to fight evil with evil with a classical counter-propaganda. Krier knows the power that architecture can wield - his monograph on the architecture of Albert Speer (Albert Speer: Architecture, 1932-1942) remains one of the most frightening architectural books I've yet seen, if there can be such a thing as a frightening architecture. He exposed fascism in all of its most seductive displays, at once explaining how the movement could wield power over so many followers, and why there would be a ban against classical architecture itself in the aftermath of the war. One could read hundreds of post-war philosophers without ever arriving at such a realization. Krier believes that classical architecture is a powerful cultural force that can also be used for good, that it is absurd to deny ourself this force because it was used to evil ends, and concludes as such his review of Speer. There is nothing so epic in this new book, although Krier dedicates an entire chapter to a plan for Washington D.C. that would "complete" the city (a plan he also displays on the cover), which shows us where his loyalties lie. What he doesn't seem to know is how dangerous the power of propaganda is, and how using it may be feeding the very process he wants to denounce.

Hence, the most problematic issue with this compendium of Krier's career is the medium itself. Krier presents drawings of an architecture that is rationalized and purified, playing it safe in order to rebuild architecture on its foundations. The great eclectic architecture of the 19th century, and the early 20th, is left out. That does not demonstrate confidence in one's belief in laws of architecture, and will not provide anything greater to a new generation of architects than an alternative propaganda that may tap some deeper feeling, but won't give them any arguments against other fashions that violate the laws. It also won't give them the confidence to radically apply the laws in order to invent architectural patterns that meet the needs of today's society, whatever you want to call it. (Post-post-modern? Ultra-modern? Webbed?) Krier may not have realized that modern architecture is a product of such propaganda, the result of architecture no longer being practiced by artisans for the benefit of their local community, but by writers and graphic designers trying to come up with the flashiest image they can place in a magazine. The quality of the building is irrelevant if the magazines drive your business.

Much like the medium created modern architecture, the medium also created medieval and neo-classical architecture. The information technologies of Gothic churches were primitive, but extremely complex. Neo-classicism could use printing, and that made mass propagation of patterns possible to the extent that these patterns were translated into drawings. The revival of the laws of architecture that Léon Krier dreams of will likely need a new medium, one that is characteristic of our society, to be accepted as evident. Until that is invented, Krier has done us all a great service by destroying the temple of modernism, leaving at least a clean slate and the right principles to start over.

Comments

I've read this book some years ago, and one of its most incredible parts was the final chapter, in which Krier describes all the rules that should be applied in order to create a perfect neighborhood: pages and pages of rules, just trying to recreate something that was born with no rule at all!

Pinning the revival of classicism on Krier is not entirely accurate. Henry Hope Reed was fighting against modernism back when Leon was just making the pilgrimage to Unité d'Habitation he credits with his personal development. Reed was just as charismatic in the 50s, and his well-written and cutting op-eds in Perspecta and elsewhere pushed people like Venturi and Rudolph to take a look at the past. Krier did lay the groundwork for the future of tradition, in that he was not bound by the misconceptions of 18th C. Modern philosophy the way that many of the old-style “Classicists” are. His emphasis on communities, messy harmony, and simple buildings seems to rub some neoclassical architects the wrong way. But his stuff is closer to what architecture probably should be, unlike the dreadful order of the City Beautiful.

And, I'm fond of the term "transmodern."

I get what you're saying, but I disagree that Reed is responsible for the revival of classicism. It's not enough to have been the first to denounce modernism, because everybody was doing that. It comes back to a "medium is the message" argument. Reed was a writer publishing articles. That was the medium of the 19th century. That is why no one talks about him anymore. Le Corbusier became an icon because he embraced the new media of propaganda.

In that sense, because Krier adopted the same new media in his counter-modernism, he is the one who deserves the credit for "modernizing" classical architecture. He is the one who brought it to the modern audience.